The surprise of a homeless mother and newly born baby brought misfortune

BABY ANTONIO was born on the streets.

On a steamy August Thursday, he came at 12:29 a.m. He weighed 5 pounds and 12 ounces and was purple and well developed. As hospital officials stood over him, he stretched his tiny arms and legs into the air, counting 10 toes and 10 fingers. His skin changed from purple to light brown, and he sobbed, knowing nothing about his surroundings.

A stereotype of homelessness exists: a lone, unkempt man begging on a crowded sidewalk while holding a cardboard sign. However, children under the age of six constitute the largest single population in New York City’s shelter system.

Infants are capable of causing havoc. Their births might cause entire families to become homeless or

“A quick test. “When are you most likely to become homeless?” questioned Allyson Crawford, CEO of Room to Grow, a non-profit that assists low-income parents with newborns. “The correct answer is 1.”

New York City has a list of official causes of homelessness, and high on the list are eviction, overcrowding, family discord and domestic violence. Look closely and pregnancy is often intertwined, advocates for the homeless say.

A woman becomes pregnant, and suddenly, the two-bedroom apartment she is sharing with her family becomes too small. Faced with added responsibility once the baby is born, she falls behind on bills and rent. Family tensions rise. She argues with parents or with her partner. She may become a victim of domestic violence. Too often, she ends up moving into a shelter and so does her child.

Steven Banks, the city’s commissioner of social services, said infants are often “the tipping point” for families on the verge of losing a permanent home. “The main driver of homelessness, irrespective of pregnancy, is the gap between rent and income,” he said. “However, the birth of a new child is a background factor.”

When Antonio was a week old, he was one of 11,234 children under 6 living in a shelter system that houses about 60,000 people daily. There were 1,164 children born into the shelter system last year, up from 877 in 2015, according to data obtained by the Coalition for the Homeless.

IN THE BROOKLYN shelter where Antonio lives, his family stays in what amounts to a studio apartment, with a small kitchen and bathroom and two sets of bunk beds in the main room. His 4-year-old sister and 14-year-old brother sleep on one of the bunk beds, the little girl below, the teenage boy above. His parents, Shimika Sanchez and Tony Sanchez, squeeze into the bottom bunk across the room, while he sleeps in a brown crib.

Ms. Sanchez said the couple put nearly all of their belongings in a storage unit that costs $213 a month.

Three strategically placed fans cool the room, though sometimes, on scorching days, they only push the hot air. Her son does homework and studies at a small dining table flush against the same wall where his parents sleep.

Ms. Sanchez, 34, had a difficult pregnancy and had been diagnosed with pre-eclampsia, a condition that can cause dangerously high blood pressure and can be fatal to the mother and fetus. Ms. Sanchez, a home health aide, said a doctor had encouraged her to stop working.

Mr. Sanchez, 36, is an ex-convict and has trouble finding well-paid positions. He works odd jobs, like demolition on construction sites.

They have been trying to save enough to move out of the shelter. They argue all the time about money.

The lack of money is exacerbated when a child is born, and can have an even greater impact on homeless mothers. Several studies have shown that homeless pregnant women experience high rates of depression.

A 2011 study of homelessness in 31 cities, including New York, showed that infants born to homeless mothers are at greater risk of longer stays in the hospital. Children begin to show signs of emotional problems and developmental delays by 18 months. They also have poorer nutrition and go to fewer preventive medical appointments, including for vaccinations, according to the study published in Pediatrics, the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

City agencies have started to grapple with the problem. Officials have taken steps to raise awareness about crib death in shelters. They also have created a questionnaire to assess birth weight and signs of developmental delay and have started several pilot programs, including one to promote reading to infants. Robin Hood, the antipoverty charity, is leading two pilot programs focused on combatting maternal depression and encouraging the bond between mother and child.

MS. SANCHEZ began considering moving into a shelter four years ago after Bella was born, and Ms. Sanchez’s parents, who were never married, reunited romantically. At the same time, Mr. Sanchez was months away from being released from prison, and Ms. Sanchez wondered how her family of five would fit in her mother’s three-bedroom apartment, where her two younger sisters and a niece were also living.

She has been living doubled-up most of her adult life. In 2012, the apartment she shared with her mother and two sisters in Far Rockaway, Queens, was destroyed in Hurricane Sandy.

For several months, the family lived in a hotel room paid for through the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Then they moved to a house in Brooklyn with a Section 8 voucher, a federal rental subsidy. They had lost everything.

“We said, ‘At least, we had our lives,’” Ms. Sanchez’s mother, Mary Brown, said. “We had rough times. We all did. Me and my kids.”

Ms. Sanchez entered a city shelter in March 2017, and her husband joined her after he was released from prison that fall.

A high school dropout, Ms. Sanchez earned her equivalency diploma and then a certificate in medical assistance from Sanford-Brown Institute, a for-profit college that paid a $1 million fine for misleading its students as part of a court settlement with the state attorney general.

“I pay $300 a month in school loans,” Ms. Sanchez said.

ON A TUESDAY morning in early August, Ms. Sanchez, who was 33 weeks pregnant, waddled into the Brookdale Hospital waiting room with her husband and daughter for a prenatal checkup. Mr. Sanchez lifted Bella, buried his face into her stomach and spun around.

“They’re going to be surprised I made it on time,” Ms. Sanchez said as she settled into a seat.

Mr. Sanchez’s phone rang. It was a call for another odd job. Mr. Sanchez’s criminal history, including three burglary charges, limited his job choices, and he could not pass up a chance to work. He had to go, he told his wife.

He kissed her and kissed his daughter. “You have money?” he asked, digging his hands into the pockets of his khaki shorts as he stood in the doorway of the waiting room.

“Yes, you gave me money,” Ms. Sanchez said.

The chilly waiting room had a dozen or so chairs in a semicircle. Everyone joined in each other’s conversations. One woman was breast-feeding her baby. A man looked at his phone. When Ms. Sanchez stepped out of the room to have her blood pressure taken, her phone rang and Bella picked it up.

“Hello, what’s up?” she said. “I can’t get mama on the phone because she’s out there. I’ll call you back.”

“Who was that?” someone in the room asked. “My daddy,” she said. Everybody laughed.

When Ms. Sanchez returned, she talked about how much she missed a job she had held as a home health aide. She was proud that she had found ways to befriend older white people who had misperceptions, or even racist views, about black people. “You become someone they have to rely on,” Ms. Sanchez said.

Bella grew bored. She tried to dance and sang the lyrics of Drake’s “In My Feelings” over and over again though she only knew a few of the words. She took her shoes off and refused to put them back on. Her toenails were covered in chipped white and pink nail polish.

After a couple of hours, a physician assistant called Ms. Sanchez in and told her that her blood pressure was unusually high. She was scared.

Cyrus McCalla, her doctor, decided she needed to remain in the hospital overnight. Usually, Ms. Sanchez could calm herself, slowly breathing in and out. But her blood pressure was not dropping, and her condition grew more serious as the day wore on.

By 4:05 p.m., she had been transferred to a hospital room in the labor and delivery wing. “I need to call my husband and tell him I’m here,” she told a nurse.

She called her mother to pick up her daughter, who had climbed on the hospital bed and rested her head in her mother’s lap.

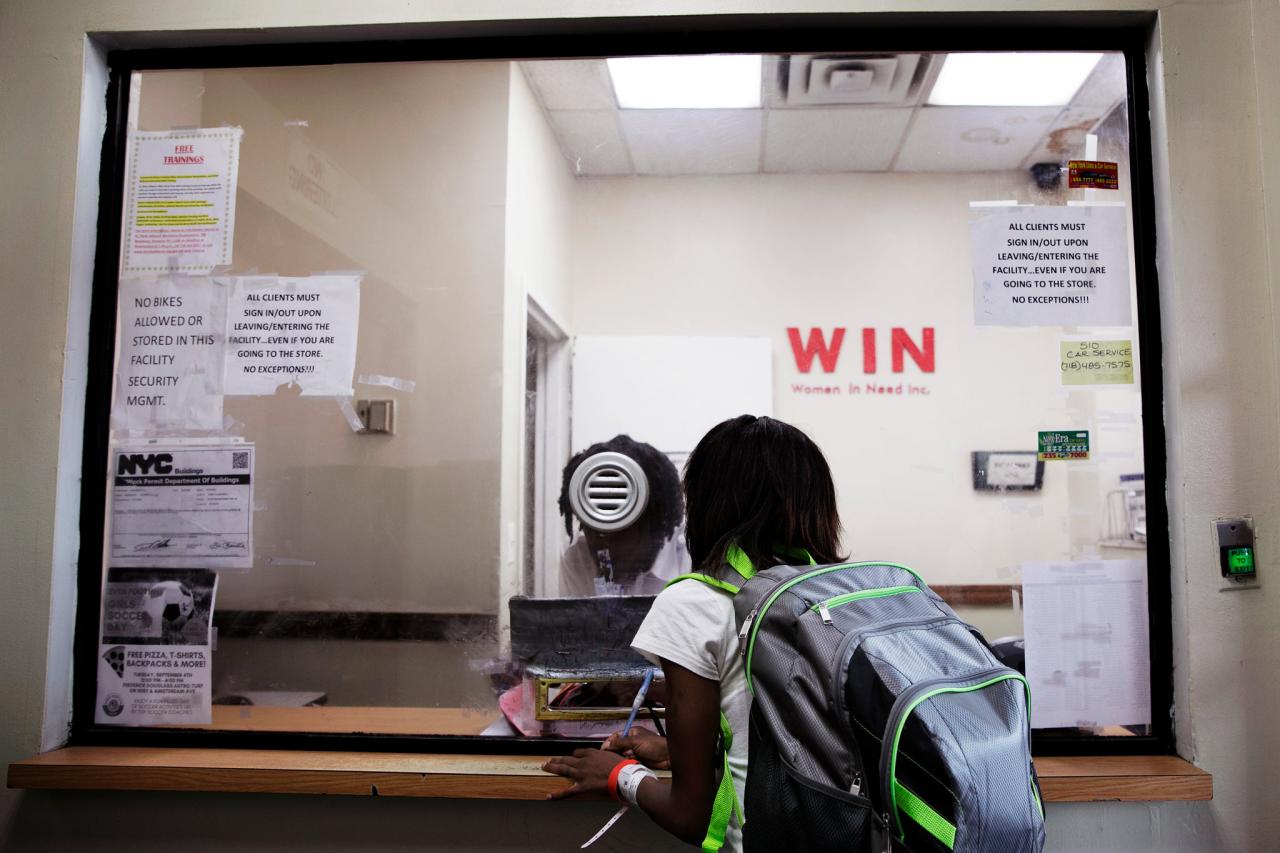

Ms. Sanchez tried not to panic, but she thought about her room at the shelter. She fretted about Antonio’s crib. Win, the nonprofit operator of the shelter, required Ms. Sanchez to use a crib it provided. She had taken a photo of the crib, which was metal and painted white. It looked like a shopping cart, she said, without the handle. It sat low to the floor, and she worried that mice could get in. “How does that pass a safety test?” she asked.

Ms. Sanchez did not give birth that day.

Naturally petite, she weighed just 97 pounds. Baby Antonio weighed an estimated 4 pounds. She had delivered her daughter 10 weeks early, and doctors were trying hard to avoid a similarly premature labor. It was her second overnight hospital stay in two weeks.

OVER THE NEXT three weeks, Ms. Sanchez had contractions that forced her to go to the hospital and derailed several outings, including a night out with friends at Red Lobster and shopping for baby clothes.

But on a Wednesday in late August, her doctor decided that Ms. Sanchez should be induced. Ultrasounds showed that Antonio weighed more than 5 pounds, close to 6.

Ms. Sanchez arrived at the hospital with Red Lobster takeout she had bought the night before. She wanted to make up for the Saturday night dinner she had missed.

The next hours were a mix of happiness, anger and sadness.

As the contractions came on, Ms. Sanchez joked with friends and family and yelled at her husband on the phone. Sometimes, she joked with him, too. “It’s going down, but not in the DM though,” Ms. Sanchez said, laughing as she referred to Yo Gotti’s hit about online flirting, “Down in the DM.”

Her sister, Chanell Brown, 29, was in awe. “Are you in labor? The reason I’m asking — you’re on the phone and in labor. That’s gangster,” she said.Then Ms. Brown began crying uncontrollably, wiping tears from her face. A month earlier, she too had moved into a city shelter with her 2-year-old daughter. And she was pregnant again. “It feels like I’m struggling more now with a kid,” she told her sister.

That night, Ms. Brown wanted to witness the birth of her nephew, but she was worried about missing the shelter’s 10 p.m. curfew. “I don’t want to leave, but I don’t want to get in trouble,” she said.

“You have got to do what you have to do, Chanell,” Ms. Sanchez said. “You have to get it together, mama. You have no control over this moment. You have to be, like, ‘This is something I’m doing for me and my baby.’ You have to think of the outcome when you’re able to walk into your own house.”

Ms. Sanchez told her that some day they would both be out of shelters, and their children would spend the night at each other’s houses.

It wasn’t long after Ms. Brown left that Ms. Sanchez gave birth.

She nestled Antonio close to her breasts to feed him. Mr. Sanchez took off his tank top and laid Antonio to his bare, tattooed chest. “He’s so small,” he said, smiling and glossy-eyed.

TWO DAYS LATER, Ms. Sanchez took Antonio to the shelter. Right away she spotted what was missing and what had been added to the room. She had asked the staff for a portable air conditioner, which was not there. But there were two identical cribs that resembled shopping carts in the middle of the room, side by side. “I didn’t have twins,” she said, shaking her head.

Her husband was out looking for work. “Stop telling me you need to stay out to make a few more dollars,” Ms. Sanchez said to him on the telephone.

“I need you here.”

Someone had taped a flier about safe sleep for babies on a wall.

A maintenance worker knocked on the door and took away the extra crib.

“What’s the baby’s name?” the worker asked Ms. Sanchez.

“Antonio,” she said.

“That’s my middle name,” the worker said.

As Antonio lay on a bottom bunk, between two pillows, Ms. Sanchez cleaned up. She cleaned out the refrigerator. She sorted through clothes donated by friends and some she had bought at Cookie’s Kids.

She folded baby blankets and onesies. (More supplies, including a different crib, would arrive later with the help of Win, the largest provider of family shelter in the city.)

“The Jeffersons” played on a small television atop a dresser. It was the episode in which Lionel Jefferson, the son of a wealthy businessman who owned laundromats, and his fiancée called off their wedding after arguing over a prenuptial agreement. At the end of the episode, the couple made up.

Ms. Sanchez laughed. If only her real life were as easy. If only her family lived in “a deluxe apartment in the sky.”

She rocked Antonio and kissed him until he fell asleep, limp in her arms. In about a month, she announced, she planned to return to work.

“I’ll make sure before you turn 1 we’re out of here. All of us,” she told a sleeping Antonio. “We’ll bust out together.”